[Watch the video on Youtube here]

Michael Hauge and Mark W. Travis: One of the things about structure that changed more than anything for me because I didn’t realize this for the first 10 or 15 years that I was a consultant and lecturer and that is I always thought of plot structure, meaning the sequence of events and the things that happened and that’s sort of externally, and it is a plot structure and there are certain key things that need to happen at 25% and 50% and 75%, but the revelation to me was when I realized that the inner journey the character takes also has a structure and it’s exactly the same structure.

Markus Redmond: You cannot judge your character. In fact you have to think of yourself as your character’s attorney. You have to plead your case or the case of the character to the audience. You can’t do that if you’re judging the character and I took that with acting and I also took that into my writing as well. Everybody is coming from a place where they think they’re doing the right thing.

William C. Martell: We as the audience jump onto the screen and become the protagonist in the story and a good story has some sort of a fantasy and it doesn’t have to be a positive fantasy that we want to explore in our life so we skin jump and we are Elliot riding is bicycle with ET and it flies. That is one of those moments where if you were to turn the camera on the audience and watch what watch (the audience) they would all be just overjoyed because we’re all Elliot in that scene for that moment. If we’re looking at a movie, we can become Indiana Jones and do the amazing adventure thing and we basically jump from the audience onto the screen which means we need a character to jump into. A good story is about a character that fulfills some sort of dream fulfillment, some sort of fantasy the audience has and a the reason why a film is a hit is because it ends up hitting the dream fulfillment elements of a lot of people. If you can figure out the Zeitgeist of what the audience or what people are dreaming about right now, that’s that thing that’s going to pull us onto the screen.

Karl Iglesias: The first thing you have to understand about dialogue is that it’s got to be connected to the character’s desired line in the scene. In other words, if a character has an objective (an intention in the scene) the dialogue has to match that intention. What I see a lot of times especially with exposition and information is that a character is saying all that information and you can tell that it’s really the writer’s objective, in other words the writer wants to wants the audience to know this information because they think okay the audience needs to know this and this and this and this, so the character is going to say this and this and this and this. That doesn’t work because scenes and dialogue are about a character’s intention in the scene. Everything a character says is matched to what that desired line is.

Peter Russell: The device by which we make a character sympathetic is to show their wounds because as human beings we’re not going to be interested in good looking, perfect people who are making a lot of money and they’re great and everything they do…who gives a [____]! We want to see people that we can identify with because that’s not us. We’ve got problems, right. I’ve got problems, right. I want to see my problems and somebody else with problems, dealing with problems. You can say Well, a show like Riverdale doesn’t do that but they do. There’s fantasy shows (absolutely fantasy shows) where that’s not the case but most of the time you do want to see a wound. That’s what likeability really means Oh they’re like me, they’re screwed up, they don’t have it all together, wish I did, maybe they’ll get it together.

Jill Chamberlain: A story, there’s a connection where between the parts this happens, which leads to that happening, which makes it ironic, when this other thing happens, there’s a connection between the parts. Another way I can put it is if I can take your protagonist out of your script and put a completely different one in and maybe with a couple of tweaks it works just as well, you have a situation my friend, not a story. I shouldn’t be able to do that. If you’re telling a story, if I were to take your protagonist out, it would no longer work. A story is unique to your protagonist. There’s something, there’s a unique journey, a reason why you (the master of the universe here) has put this character on this path, there’s something in that character that you’ve chosen to do this particular plot in order to bring out something in them. If I can put just another character in, and it works just as well, that’s not a situation, that’s not testing anything specific to the character, it’s just an arbitrary situation that you put a character (you put someone into) and that’s what most people do, that’s the way a lot of us start. It doesn’t mean that it’s not a fixeable situation.

Shannan E. Johnson: I think one of the biggest mistakes is jumping into something that’s not going to teach us anything so it doesn’t matter to the story, but you think it’s cool. Understanding that those first few pages are about the setup, this is me gathering information about the character, about the world, I’m going to start making assumptions about what’s going to happen. I’m not looking for the inciting incident on page one but I am looking for things that are intentional and things that are going to help me understand at least who this character is. That’s why you’ll see a lot of action films open with an action scene because you’re teaching me the skills that this protagonist has. You’re teaching me that they know how to fight, they’re usually the good guy, they’re usually the winner or whatever other information that you need me to know and now when the inciting incident does happen and they say you’re going to have to go off and save the world, I believe they can do it because you’ve already shown me that they can.

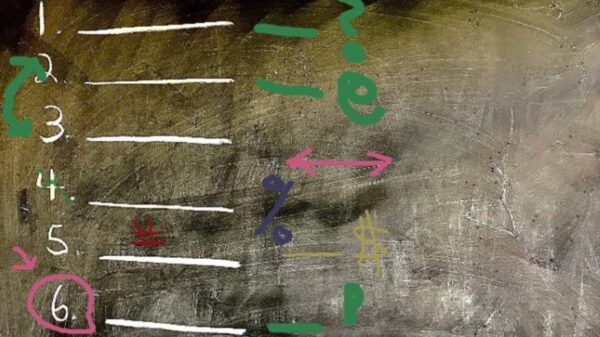

Glen Gerrs: Writing is a process of questions that, if I could, there’s a couple of things that I wish I could get tattooed on the inside of people’s eyelids that they knew:

-Think in scenes

-Writing is a process of questions

It’s not a thing you have to fill out, it’s not a form that you have to fit into. Writing is a question, it is always a process of having something. It could be just I want to write a western or I want to talk about how love hurts or I want to talk about about how love saved my life. Whatever it is that you start with then you start to ask questions:

-How am I going to tell this story?

-Am I going to tell it through a character who gets it or a story who doesn’t get it?

Everything is going to be a choice. Every question that you ask, if you write down that question:

-How am I going to tell this story?

-Who is the main character?

-Everything is a question and those questions are:

-Who is it about?

-What do they want?

-Why can’t they get it?

-What do they do about that?

-Why doesn’t that work?

-How does it end?

Those six questions basically will help you write anything.

Pat Verducci: Transformation in a story is a key element and whether it comes through your main character or your main character changing everyone else, it doesn’t matter, it’s just that transformation is actually the purpose of a story. It’s actually the purpose of a story because the reason we tell stories is to actually understand ourselves better and that insight is a transformation for us.

Christopher Vogler: Now that you have loaded up your equipment and reassurance and you know where you’re going, you know what you want, you’ve faced your fear, you’ve been reassured, now it’s time to get up and go. When I was working for the movie studios, especially for Disney, they talked about like an airplane taking off and they said you’ve spent all this time in what they call the first act, the first three or four or five movements. Those first steps, you’ve loaded the plane up and you’ve fueled the plane and you’ve told everybody to belt their seat belts and all the safety things, now get the wheels up and get the plane in the air. This is the feeling of lifting up that you get when all the preparation is ready and now we’re going into that new world or special world as Joseph Campbell calls it. He says every story he ever looked at seems to take place in two worlds, either environments or states of being, two different states of conditions. Now we’re going to launch into that special world and this is a big turning point in a story. That signals the audience all the prep is done now we’re going for it and the audience likes that and they feel a nice lift there and sometimes it’s backed up by change in the music or the change in the energy of the scene to say We’re leaving Kansas, we’re leaving the ordinary world and now we’re going someplace very, very different and exotic.

Advertisement – contains affiliate links

(As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases)

More affiliates:

Camera we use for interviews – https://buff.ly/3rWqrra

Sound we use for interviews – https://amzn.to/2tbFlM9

Other books on Amazon that Film Courage recommends – https://buff.ly/3o0oE5o