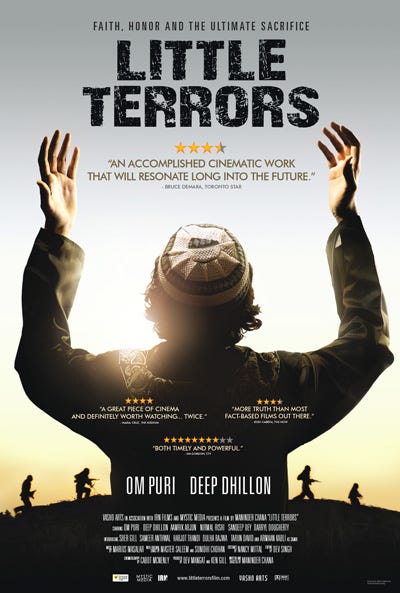

Writer/Director Maninder Chana – LITTLE TERRORS Movie

Film Courage: Where did you grow up?

Maninder Chana: I was born in a little room of our house in India in a village called Mandhali in Northern Punjab. I grew up there till I was 5 and that’s when we were hauled off to Canada. I didn’t really have much say in the matter but we ended up in Windsor. And that’s primarily where I grew up till I moved to Toronto in my early 20s.

Film Courage: Which of your parents do you resemble most?

Maninder: My mother was cute, as people would tell me growing up, so I’m going to say her. I have her stubbornness and my Dad’s workaholic determination. Both good traits. And both their senses of humor to temper things.

Film Courage: Did your parents encourage a creative job/work for you?

Maninder: I worked in my Father’s factory here and there from the time I was 10. He bought us instruments and I play a few and that was really what I wanted to do out of the gate but it was discouraged other than as a hobby. So the short answer is ‘no.’

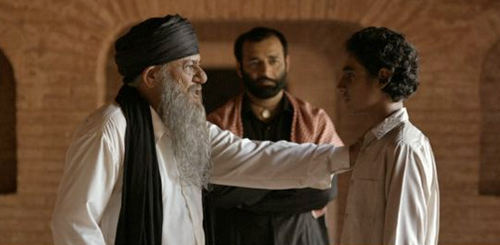

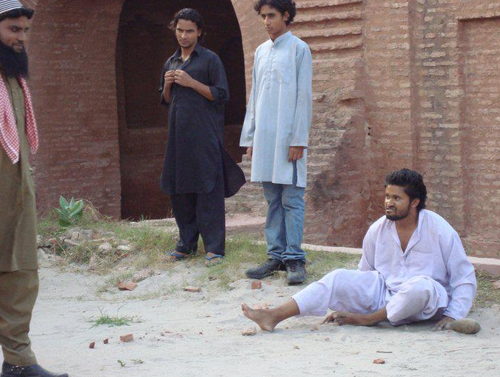

Scene from the movie LITTLE TERRORS by Writer/Director Maninder Chana

Film Courage: Did you go to film school?

Maninder: No. When I wrote my first screenplay I was 23. When I finished it months later, I took out one of those Syd Field books on writing screenplays from the library when I went to edit the draft. I realized I had already done naturally what the directions were in the book. So I took that as a good sign. Directing developed naturally as a course out of having a comedy troupe in the late 90’s and having a broadcasting degree. The rest was a lot of trial and error. But as long as you keep trying you begin to wrap your head around all the elements that go into making film. You don’t need film school. You need to believe and have a willingness to learn and the discipline to teach yourself and the mindset to grow.

“Director Maninder Chana shows a deft touch and a deep understanding of human nature in this tour de force film. ‘Little Terrors’ perfectly blends western story telling with Indian sentiment and locations, it’s a must see!”

Lindsay Moffat, Producer (Syfy, Lifetime, Hallmark, etc.)

Film Courage: Do you begin a script with the beginning and ending in mind?

Maninder: Every tale is different. I have several screenplays I write at the same time, some will get finished, some peter out if I decide they aren’t going anywhere. One of the ones I’m working on at the moment is from a dream that played out completely beginning to end in my sleep. So I got up and made notes from it and worked it out that way. Other times, if there’s a twist at the end then you work backwards from that. You are always making notes. Always before, during, after every draft. However, a couple of the other screenplays I’ve been hammering out, I wrote short stories to first in order to develop the main character’s voice and the overall plot structure. It was something that I really like and I think I’ll keep doing that. Time wise it takes longer to finish but I’ll also have a short story collection at the end of it on top of the screenplay. Another one I worked on was an unfinished novel. So it all varies. Some people use scene cards and programs to plot out their storyline, but I’ve kind of kept to letting the excitement of writing and discovery happen on its own.

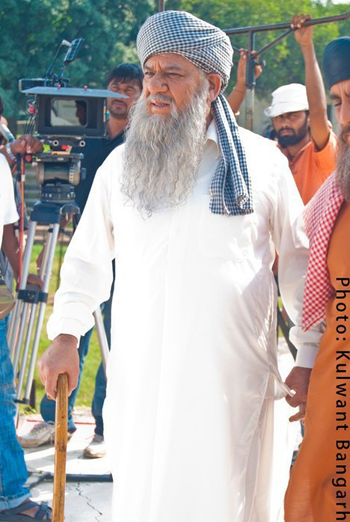

Scene from the movie LITTLE TERRORS by Writer/Director Maninder Chana – Photo by Kulwant Bangarh

Film Courage: What’s right with the world?

Maninder: A lot more than any of us care to admit to.

Film Courage: What are the advantages to being a Canadian filmmaker?

Maninder: This is a tricky question, honestly, and I’m going to hold a lot of what should be said back. Most people in the industry know the situation. There’s a good interview with Matt Johnson in a recent NOW magazine interview that echoes a lot of my sentiments. Things I’ve said for the last decade of trying to get government funding here. I fall on the opposite side of the line. Most of my funding has come privately. I’ve only done one project that had some OMNI documentary funds but I had another producer who brought those in.

I’ve been lucky enough to find investors who believe in me, which is what real investors do: they buy into the person not necessarily the idea. So it’s hard for me to speak to that because I’ve never been in the clique that gets to go to that trough over and over again.

There’s a very limited pool of finance in the UK. To be honest, it’s a very clubby kind of place. In Hollywood, there’s a great openness, almost a voracious appetite for new people. In England, there’s a great suspicion of the new. In cultural terms, that can be a good thing, but when you’re trying to break into the film industry, it’s definitely a bad thing. You know who said that? Christopher Nolan. That’s what took him out of her Majesty’s secret film industry. Sadly, you could say the exact same thing about our funding system and you’d be bang on. That’s why I kind of feel LA calling me at this point, especially now that I have west coast representation.

I could go on at length but the NOW article I mentioned speaks to a great part of it.

But there are good tax incentives when it comes to labor. CAVCO, for instance, is a great incentive and every production tries to take advantage of that. There are local bonuses like shooting in Hamilton that give you an extra ten per cent and BC just upped its game with some local incentives too. So it’s not all bad. The low dollar helps the industry. We wouldn’t have so many contenders at the Oscars: i.e. Brooklyn, the Revenant, Room that were shot here if it wasn’t for the falling looney and the tax incentives I mentioned. If the pendulum swung the other way it would be a completely different story.

LITTLE TERRORS is Now on iTunes!

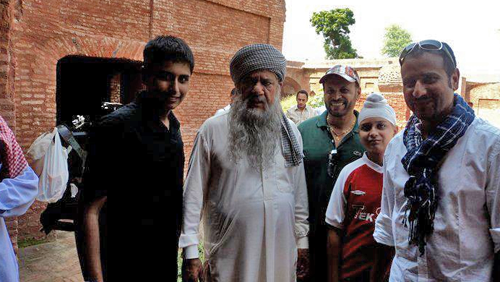

Scene from the movie LITTLE TERRORS by Writer/Director Maninder Chana

“Even mundane bits of literature can inspire you to come at ideas a completely different way than before.” Writer/Director Maninder Chana

Film Courage: Two writers who have inspired you (any genre or medium)?

Maninder: You could probably add a couple of zeros to that list and I still couldn’t narrow it down. I have an English degree so I read everything you have to read to be considered well read. And then when I got my degree I didn’t pick up a book for a year. I was exhausted. My eyes hurt. But since then thousands more. So it is hard to narrow down, even mundane bits of literature can inspire you to come at ideas a completely different way than before.

I can’t remember if George Carlin ever wrote a movie but I miss that guy in terms of crafting a joke that would make you think. Part of it is in the delivery but the real nugget, the thought, the truth of the statement comes from an entirely unique place. My background is in comedy so I just align myself with people who can make you laugh and think at the same time. Nobody did it better than Carlin before or since. I wish that guy had written films or at least been around for another Bill and Ted’s movie.

The only author I’ve read all of his books (only because there’s so few) is J.D. Salinger. If Catcher in the Rye hits you at the right time as a teenage boy, it sticks with you for the rest of your life. And that makes you want to affect others in the same way.

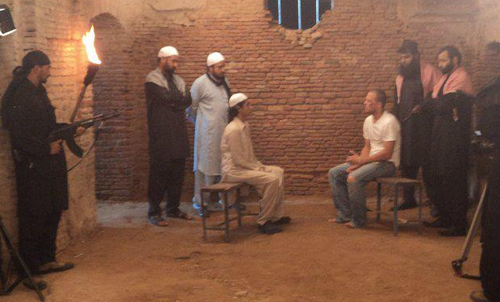

Scene from the movie LITTLE TERRORS by Writer/Director Maninder Chana – Photo by Kulwant Bangarh

Film Courage: What prompted you to want to tell this story in your latest film LITTLE TERRORS?

Maninder: I was actually approached with the idea. I was producing a sci-fi feature at the time and my producer’s friend came to visit set to pitch the project. I thought I was going to be pitched some Bollywood song and dance musical and so I was set to say no. But the crux of the idea was intriguing. I developed it out of his very rough idea.

I knew I could bring something to it for several reasons. I worked as a journalist so I’m buried in the news of the day and well-versed in 9/11 and the aftermath of all of that. I am also fascinated by religion and how it shapes our world and our personal viewpoints. I’ve read the Quran. Plus I actually dated a beautiful Muslim girl for five years, so I knew I could bring something to the table that other writers or directors couldn’t because of my experience being in and outside of the religion at the same time.

Film Courage: How long was the idea floating around in your head before you started writing LITTLE TERRORS?

Maninder: I let the idea simmer for a while and did a lot of research and went back to stories I’d remember of child jihadists, Daniel Pearl, Omar Khadr, incidents that happened during the Afghan and Iraqi wars, Osama Bin Laden’s history, recruitment strategies of Al-Qaeda, etc. There was obviously so much to draw on. Everything in the film, every incident, every character is based on something. So when it was time to write it, it was about trying to bring a lot of disparate elements into a personal journey.

Now on iTunes! – Scene from the movie LITTLE TERRORS by Writer/Director Maninder Chana

Film Courage: How long did it take you to write the first draft?

Maninder: The first draft took about eight days. When I write quick I tend to know I have something. Everything else after that is rewriting and tweaking. It’s the same in a lot of aspects of filmmaking. When you go to edit a film, you can cut it pretty quickly but it’s all the tweaking that is time-consuming. That’s the laborious bit. How long did it take to finish the final script? I’m probably still not finished in many ways. Other ideas still come to this day that I wish I’d put in.

Film Courage: How many people did you share the script with during the writing process?

Maninder: Just the producers, initially. They were both Indian guys and first-time producers so I don’t know how well they knew how to read a script but you try to write so any layman can see what your vision is. We did do a table read with a number of local actors and friends to get feedback. So including them, there were a dozen or so who saw it before I went to further drafts and polishes.

Film Courage: How long have you been planning the film?

Maninder: I’ll be brutally honest. Making this film was hell. I think of it as my Hearts of Darkness if you will. As I mentioned the producers were green so they thought that we could turn the film around quickly. I didn’t think so. So we went to India and did a preliminary scout with the plan to start hiring and shooting within a few weeks. This was, of course impossible, especially since we wanted to find a couple of stars for it. So we met with some stars. I don’t watch a lot of Bollywood films, but I was told they were famous. But in that first journey, nothing was materializing as quick as hoped so the initial plan was scrapped. But I was asked to stay on and do some scouting. I wanted to go home and everything inside was telling me to go home and regroup and come back at it properly. Unfortunately, I didn’t listen to my gut. My mother passed away while I was still in Mumbai. Two months later, one of my producers’ brother passed away as well. That began a journey into hell.

For months, I had a sour taste in my mouth about returning to the project as I think anyone losing someone so close would. But ultimately I did and the process began again. So the script was finished in January and we ended up finally shooting at the end of September. Lots of problems, lots of chaos, logistical nonsense. We didn’t have a seasoned crew. The budget didn’t allow for it. I won’t get into it, I could write a book and if I had time I would have kept a journal of all the craziness I had to put up with, but one example is that my A.D.s had never seen a call sheet in their lives and didn’t know how to break down a script to schedule a film so I had to do their job on top of mine. The sad thing is that in Canada or the States, as a director if I ask for something 20 people will run but in India, it was the complete opposite. People stood there until you yelled. I never screamed so much in my life. I found it to be an exercise in coercion rather than cooperation, which I think is India’s Achilles heel. It’s why a lot of immigrants are successful when they have an opportunity like Canada or the U.S. They were born of a different mindset the vast majority of Indians and needed to escape to a place that would nurture their ambitions.

One of the things I remained steadfast on was to keep my white DOP, despite suggestions I get an Indian. That was because I knew that a lot of Bollywood films use flat lighting to make brown faces more white (and in Bollywood’s eyes more appealing). Little Terrors, though is a film of shadows and light. So I wanted to make sure I had a strong cinematographer like Cabot McNenly on board to add depth and make the film look as American as possible. It needed that balance. And Cabot did a fantastic job on the project. Nobody who looks at it would guess we shot it for the budget we did.

I won’t get into post-production nightmares. That’s a whole another story.. we’ll be here all for eternity, if I start into that.

Scene from the movie LITTLE TERRORS by Writer/Director Maninder Chana

“There’s a little fortune cookie saying that covers the camera eye on my computer so the NSA can’t look at me naked and it reads: ‘It is better to attempt something great and fail than attempt to do nothing and succeed.’ So I constantly challenge myself. It’s the only way to know what you’re made of and learn and grow from your mistakes.” Writer/Director Maninder Chana

Film Courage: How did you pitch the script to your actors?

Maninder: Casting for the film was strange in India. In the west, we’re used to being in a room and the actors are brought in one by one. The Indian team decided to put all the actors in the same room at the same time. I said it’s not done that way. They said it’s India, which became a very sad excuse. So every kid who auditioned tried to play the role like the first kid did whom they saw do it. It was insane. And in casting others, I was told they had to be interviewed. I said people audition. You can’t tell from a meeting if someone can play the role or not unless you’ve actually seen them in something previously. So it became an exercise in futility as such in pitching the script because you couldn’t test actors the way you should be able to in an enclosed safe environment.

Stars like Deep Dhillon and Om Puri were my saving grace. Especially Deep. They were professional and used to arriving on time and hitting their marks and knowing their lines and bringing something to the table. That’s where I felt at home because we spoke properly about character and motivations and the language of a film set. For Om, we discussed a dying elder of a training camp, as one of Osama Bin Laden’s right-hand men had been. And for Deep as the man wanting the old guard to fall so he could rule with a more iron fist in a sense, what we see with ISIS now and Al Qaeda struggling to stay relevant.

For the kids, who were newbies, I gave them sense-memory exercises to build their characters. It’s a thinking exercise and I know for a couple of them it made their head hurt. But it is a thinking man’s game so…

For Aamrik Arjun, who didn’t speak fluent English, at one point I gave him simple dictation and annunciation exercises like that ‘Peter Piper picked a peck of pickled peppers.’ Other actors I was rehearsing with saw me do this and asked me to write it down for them as well. So Aamrik would come in and show me his progress. It was funny. He did a great job with his English.

There were also a bunch of novice theater actors that I had to beat the overacting Bollywood out of as well.

So pitching characters and script to them was a multi-layered job. As it always is. But those are a few examples, there’s tons more.

“Little Terrors is engaging and slick work from Maninder Chana. I was hooked from minute one. Great film making from the emerging Canadian writer/director.”

Jonas Quastel, Writer/Director ‘Forced to Fight’

Film Courage: Much of your prior films have been comedic shorts. How much of a different mind set or ‘head space’ did you go to when writing and planning LITTLE TERRORS when much of your prior work reflects a playful, light, dark comedic elements? Were you a bit nervous taking on the challenge of LITTLE TERRORS?

Maninder: No, it wasn’t nervousness, per se. It was a welcome challenge. I just didn’t know how much it would be given the situation but there’s a little fortune cookie saying that covers the camera eye on my computer so the NSA can’t look at me naked and it reads: ‘it is better to attempt something great and fail than attempt to do nothing and succeed.’ So I constantly challenge myself. It’s the only way to know what you’re made of and learn and grow from your mistakes.

In terms of comedy, yes I did a lot of comedy but I have a very serious side like any comedian does. That’s what people don’t understand and why some of the best actors come from the comic world. Being funny is a serious business. There’s truth in that cliche. Plus I have viewpoints on the world that I want to speak to. So it’s very easy to go to that headspace but like I said in many ways you have to be a somewhat dark person to do comedy. A lot of comedy comes from a place of pain, but that’s also a place where you find strength. And the film, in the end, is about overcoming pain with strength.

Film Courage: Which character in LITTLE TERRORS is the most pivotal to the story and why?

Maninder: Most people would think Samih, the young protagonist of the story. But he’s really not the protagonist. He’s an anti-protagonist, letting life carry him, looking for someone to give him purpose, just like a lot of these lost kids that are brought into the jihadist fold. The protagonists and the antagonists in this really are the characters I built around him: the four father figures. In the camp where he’s trained, he has a grandfather and Father figure in Om and Deep’s characters respectively. They are playing their tug of war with his young mind, poisoning it to the point that he’ll do anything to please them. And then comes another Father figure, more a brother really, replacing the one Samih lost, Steve, the journalist who puts a seed of doubt in the boy’s head. Follow this with a real Father figure, Amir, who treats his daughter with kindness and not as property, who sees something in Samih’s struggle that still resembles humanity and starts to play a very dangerous game of trying to convince him not to go through with his mission.

To me, they represent one overall character because Samih is a very internally conflicted soul. The things he’s going through are really playing out in his mind so what these characters represent ultimately is his thought process leading towards his final decision.

Film Courage: How does LITTLE TERRORS go back to the roots of Islam and re-frame the beliefs from an outsider’s perspective?

Maninder: This is an unpopular thing to say but I’ve always believed that if we only ever read the first page of anyone’s bible, we’d be a better race of people. For example, God created the earth in six days and on the seventh he rested and looked his work and said it is good. I’m paraphrasing but what do you get out of that? That God’s real message is to go forth and create. There is nothing about destruction. And it’s not only to create but like God to afterward, look upon the beauty you’ve created and enjoy it, share it. The Torah starts the same way, as does the Quran.

So in this sense, I went back to page one and in this case, the Hadiths, the sayings attributed to Muhammad. The Quran is the Quran but the man is the man. So it was important to show Muhammad as a prophet of thoughts and words and deeds, instead of some bearded heretic inspiring jihadists to strike the infidels, as so many in the western world perceive him to be. This is also unpopular but man by his own definition is a flawed creature. That’s what makes us interesting. Muhammad, before he started putting anything down, thought he was going mad, until his wives pushed him to start to articulate his visions. That humanizes him in a way and makes him relatable, even now. He was working out his demons, which is the real jihad, the conquest over self, which is also a very Buddhist thing, which is also a very Christian thing.

Little Terrors is divided into four chapters and two book ends, each of which is proceeded or followed by a saying from Muhammad. By doing this, I thought, without preaching, the difference between Islam and the bastardization of the Quran, was left for the audience to determine. Too many times when Muslims try to defend their religion, they simply say it’s a religion of peace but they never tell you why. My hope is that this is a step in answering this question for the masses.

I think it’s terribly sad that the individuals/entities who got us into the Iraq war, not a one of them read or probably still has read the Quran. Sometimes to know thy enemy is to know thy self and when you know thyself the choices become apparent and the path clearer.

Film Courage: Were there any scenes which you wanted to show or decided not to omit because you felt it would offend viewers?

Maninder: We did cut out some stuff because of time issues, but there’s that saying that films are never finished, they’re abandoned, so there are things you wish you could put in. The quick answer though is no. No matter what I did I knew the film would offend some viewers. But you have to speak truth to ignorance and let the chips fall where they may sometimes.

Film Courage: Where did you film LITTLE TERRORS?

Maninder: Several locations throughout Northern India including Fatehgarh Sahib, Patiala, Rajasthan.

Film Courage: Can you share briefly your first day on set?

Maninder: It was India. So everything was later. IST (Indian Standard Time) is when we started. It continued that way because the Indian team felt we should shoot 20 days straight — not a day off — which is insane. So we lost a lot of time and daylight because people were being run ragged. The first day was a learning curve I think for most of the people on set and the young actors in particular. Their scenes weren’t as strong because they weren’t used to cameras and lights and action. It took a couple of days till it clicked for them what they we were trying to mount.

LITTLE TERRORS is Now on iTunes!

Film Courage: How do you feel LITTLE TERRORS reflects the current increase (especially since 911) of Muslimphobia/Islamophobia in the US and abroad? How does this increased fear effect the film’s marketing or framing of the story?

Maninder: The element in the film – the struggle between the two elders for power at the jihadi training camp is a perfect example of what is happening right now between Al Qaeda, the old guard, and ISIS, the new, money-hungry, blood-thirsty, badly unified new generation.

I had mentioned that everything in this film is connected to a real situation. We shot film years ago and now instead of Daniel Pearl being the journalist inspiration in the story, there have been more journalists killed at the hands of ISIS in just as maddening and socially media savvy ways as we have in our film. Children are still being recruited. In Canada, the government says there have been 100, give or take, young people that have been targeted by jihadists.

So the story has taken a very surreal form in that people who’ve seen it point out to me that it feels like you predicted a lot of what would happen in the world. The truth is it was always happening. Seeing the film, you become a little more hyper aware of the parallels that always existed for the last 15 years since 9/11, in and out of the public view.

Scene from the movie LITTLE TERRORS by Writer/Director Maninder Chana

Film Courage: At any point did you want to abandon the project?

Maninder: Yes. But that’s a long story. And I did mention this was my Hearts of Darkness, right? I will say that everything I was questioned on that pushed me rethink things, I proved myself right in the end. If we had a do-over, I know in hindsight, the powers that be, knowing what they do now, would not have stood in my way. It’s good to be right, but sometimes you have to go through hellfire to get there.

Film Courage: Did anyone attempt to talk you out of making LITTLE TERRORS at any point? If so, what was their reasoning and what were your counter-statements?

Maninder: No. I did speak to some Muslim actors prior to it but they read the script (I invited a few to our table read) and they got behind it once they’d seen what I was trying to do.

Film Courage: What were the biggest challenges you had making LITTLE TERRORS?

Maninder: Like anything else, time is the enemy. We had a 20-day straight shoot, as I mentioned. Even though I argued people needed a break, it didn’t happen and I could see the crew getting more and more tired. We lost three hours each day of daylight because of just the way people operate there. That was one of the biggest obstacles because I could have shot so much more, even if it was coverage.

Film Courage: What other actors have you cast in the film?

Maninder: One of the best finds and I hope this kid gets work from the film because he’s been waiting a long time is the boy who played Mukhtar, the bully in the camp that taunts Samih. It’s played by an actor named Sameer Anthwal. He by far was the most important character to bolster the performance of the actor who played Samih. I couldn’t find the right actor. I mentioned the insane way they had me auditioning people for that part. I was being pushed to take a weaker actor for the sake of expediency. But bad casting is an exercise in futility. Then one day Sameer walked in. He was out of drama school. He came with his friends, who told me that he was the best actor at their school, even though they were all auditioning for the same part. And he was brilliant. He was it. You can tell in 30 seconds if an actor is right for a role or not. After that it’s a question of can they take direction. Those two things: their instinct and their flexibility are what determines their ability to perform. If he wasn’t in it, Arman Kabli, who played Samih – would not have given as strong of a performance. I can’t praise Sameer’s work ethic enough. Every moment we was not shooting, he was in a corner working his craft. I loved seeing that, in comparison to the actors who came from here. Sameer had an opportunity. He knew it and he worked it. Power to him.

Film Courage: Briefly describe the appeal you think LITTLE TERRORS will have for audiences?

Maninder: The film is topical, it is plausible, it is current. It will be current, sadly for a long time to come. And if you want the other side of Islam then it’s here as well. Like many viewers have told me, they had to go away and digest it before discussing it, which in this day and age of shooting from the hip and 140 character brain farts is a good thing.

I’m not on Twitter, though I think my brain farts are much more interesting than most. I just like to brain fart inny rather than outty.

Film Courage: Aside from people seeing the film, what is your hope for LITTLE TERRORS?

Maninder: Just that. It gives them hope. The hope that we’re not so different after all. That we can win this thing if we just engage in conversation rather than suspicion. You’d be surprised what talking face to face can accomplish.

The film is divided into 4 sections each opening with an Islamic saying? What are the sayings and what significance do they have for each section?

I’d rather people see the film and find out what the sayings are and determine what they mean for themselves and to themselves. I don’t want to preach to people. The best way of learning is providing an avenue for the traveler and let him/her take the journey. I will say they were purposefully chosen to juxtapose the dialogue/scenes in the film against the sayings of Muhammad.

I’ll throw just the one example – the rest you can watch the film. Ignorance and fear lead the way at the camp, along with blind obedience which is the route Samih is on. Thrown into this mix is a captured journalist whom Samih ends up befriending because of their mutual connection to a western upbringing. When the denizens of the camp pit Samih against the journalist and their new trainee fails, they execute the journalist. And in his death, I elude to the Danish cartoons, which now could be replaced with Charlie Hebdo. Deep Dhillon’s character says something along the lines of “Now they’ll know the price of mockery in the press.” It’s immediately followed by a Hadith: “The ink of the scholar is worth more than the blood of the martyr.” In this vein Muhammad is talking about education. Ignorance, which is what these martyrs (and also Donald Trump supporters) represent are on the wrong side of Islam. The educated man, the scholar, the writer (the journalist in this case), the student, Muhammad tells us, is worth more than someone who takes a life in the name of God. So who’s the worthy ones? Those that just took a life or the journalist who was trying to educate the world?

Film Courage: What have members of the Muslim community said after watching LITTLE TERRORS or even watching the trailer? How do they feel it supports their rights, etc.? Any debate over certain scenes in the film?

Maninder: I meant in a way for this to be a love letter to Islam. But I don’t think many Muslims see it that way. White people do – the people Muslims want to reach but that’s also partly I guess from the fact that I’m non-Muslim and I come at it from that perspective that moderate Muslims long to but don’t seem to be able to. I think when you are so far in something you can’t see it from an outsiders perspective. Sometimes you need someone outside of yourself to shine the light.

Sadly, I found even moderates unable to shake their questionable logic when criticizing the film. I had drinks with a Muslim girl (she didn’t drink, she ordered a pop instead) who wanted to discuss the film afterwards. I just let her speak and didn’t debate her because I didn’t want to destroy her belief system and wanted to let her feel she was heard. I listened.

One complaint was that I didn’t put attribution on the Hadiths of Muhammad. Each has a number and designation and there are some false ones out there. I made sure I had quadruple checked all those to get them right. But the problem is adding more words made no sense. One it was unnecessary. Secondly, the film is already 60 per cent subtitled so how much more can I put an audience through to read?

The other point, which made the least sense of all was that the sayings are attributed with “Muhammad, Founder of Islam.” Her argument was that Muhammad isn’t the founder of Islam, Adam is. For people who don’t know the first part of the Quran is basically a usurped version of the Christian Bible. So her argument was that Adam of Adam and Eve fame was the founder of Islam and not Muhammad. This makes no sense whatsoever. If Muhammad had not come around, there would be no Islam. Period. End of story. You can’t run religion retroactively.

So a lot of the arguments have been weak like that and I feel they’re just coming from a place of judgement and not looking at the greater good of what someone is trying to put forth: that there is a peaceful aspect to Islam that the majority of non-Muslims have no clue about.

I wish instead that Muslims who see the film would have talked to the white people in the audience that saw the film with them or raise their hands during the Q&A so we would all benefit. Instead, they remained quiet and talked to me privately. Wrong move and they agreed when I pointed that out to them. If they’d talk to the people they are trying to get their message across to to not judge them by the actions of a few, they’d see that we have to a degree.

We also had a couple of threats but that’s from people who haven’t seen the film. And frankly, you’re nobody till somebody wants to kill you.

Scene from the movie LITTLE TERRORS by Writer/Director Maninder Chana

Film Courage: How have non-Muslims reacted to the film?

Maninder: We first screened the film in Tampa, Florida which I didn’t know till after the screening is a military town. A lot of U.S. soldiers left from there for Iraq and Afghanistan.

When you make a film, you’ve seen it hundreds of times while editing. Seeing it in front of an audience is a different thing. You just see mistakes, things you wish you could change, actors you could switch out, you spend the 100 minutes kicking yourself. An audience sees it for the first time so in a way they make you see for the first time too.

When the screening was over, there was a Q&A. I stood there waiting. It was dead silent and I thought damn I messed this up. Then the first thing a person in the audience finally said was, “Your film deserves an Oscar.” It was followed by a soldier who said “Every American needs to see your film.” Then a voice echoed, “Yes they do.”

So wow! We reached Americans. And in a soldier town at that. Isn’t that what Muslims want to do?

People have told me since it came out in theaters that it made them cry. How much it touched them. Others have gone to see it more than once. And others who said they’d be digesting it for a while. A family wrote afterwards they discussed it with their fourteen year old in terms of things that might be going on in their child’s head. It was a good lightning rod for them to talk.

We got great reviews, some mixed, but on the whole positive. The Toronto Star said it was a film that would resonate for a long time to come. But the reviews to me pale because everyone’s a critic. You can’t help but be. But the personal conversations and encouragement I received from regular folks mean so much more.

Film Courage: What films which you’ve personally watched made you question your belief system? How can movies challenge one’s beliefs without overtly preaching or is this not possible?

Maninder: Early on as a child films like “Inherit the Wind” “Death takes a Holiday”, “The Last Temptation of Christ”, and just civil rights films, I guess like “To Kill a Mockingbird” “Twelve Angry Men.” Those kinds of pictures, in general make you question the world we live in and the injustices within it.

I don’t know if you can completely stop a movie from being too preachy or not. I tried. To some it’ll be too preachy. To others it’ll be fine. Little Terrors is a movie and just like any film, people will be divided. And they are. But that’s a good thing. It means you affected people. So many films you watch and forget the next day. I’m glad for a great deal of people this isn’t one of them.

LITTLE TERRORS is Now on iTunes!

Film Courage: What does LITTLE TERRORS say about the world that we currently live in?

Maninder: That we’re screwed! Just kidding. We’re only a little screwed at the moment.

Right now we live in a world that is supposedly so connected via the internet and social media, yet we’re so out of touch with reality. We don’t have conversations anymore. We don’t have debates without getting offended. We’re afraid of alternate viewpoints. We unfriend people instead of engaging them in discussions that maybe eyeopening and mutually beneficial. This is a runaway generation. You don’t believe what I believe. Well, f*ck you!

So when we talk about Muslims, especially the family that Samih is housed with in the last act, a loving, kind people who want the best for their family and society in general – that’s the vast majority of Muslims. You don’t see that portrayed in most Hollywood films, yet that’s closer to the truth than what social media would have you believe.

Instead, we have racist soundbites, anti-immigrant sentiments, Islamaphobia, terror fears that go totally against empirical evidence that shows you’re more likely to die from a piano being dropped on your head by careless movers than to be killed in a terror attack. More Americans were killed by toddlers last year whose parents left guns sitting idly by than they were by terrorists. The aura of fear doesn’t gel with the reality.

I’m not afraid of the terrorists. I’m afraid of the terrified. The inane masses who are easily mislead by jihadists, their governments and amplified mass and social media fears. Those are the things that will lead us to totalitarianism and keep this endless cycle of war going. Sadly until someone comes along and actually shows there’s profit to be made from peace, I’m afraid little will change.

Film Courage: Where is the film available to watch?

Maninder: It’s available in a number of places if you missed it in Theaters. iTunes, Vudu, Amazon, Xbox, Google Play and Vimeo on Demand. There’s more coming I’m told.

Film Courage: Having co-hosted a podcast on religion, why does this topic fascinate you?

Maninder: Yeah, I co-host a podcast called the R-Word with Sean Sinclair-Day, who is a comedian, actor and journalist. He’s also an atheist with a very sardonic touch. I’m more witty, of course. We’ve been doing it for a couple of seasons with the aim to turn it into a television show.

Religion is fascinating in all its factions. I don’t think any one particular faith has the market cornered on crazy. These belief structures and cliques we’ve amassed effect every aspect of politics, policy, social attitudes, from the kitchen to the bedroom, from nuptials to divorce, to the way we’re laid to rest. These ideals have been handed down and codified as truth even though a lot of it stems from vivid imagination.

There’s just an insanity in putting faith in something someone you’ve never met wrote down thousands of years ago to guide you from birth to death when the only constant in this world is change. Those who refuse to change are left behind. Yet we hang on to so much that keeps us tied to false doctrines that allow us to impose self-righteous judgement on others. How can so much evil sprout from a tree of wisdom whose roots are supposedly ground in love?

It’s that dichotomy that is so interesting. Faith is interesting and why people cling to it despite immeasurable evidence to the contrary.

In Little Terrors, Om Puri tells the youngsters that all children are born to the perfect faith: Islam. But they are led away from it by their parents, society, etc. This is, by any real stretch a false analysis. Just as it is false to say a child is born racist – you have to be taught hate, so too do you have to be taught religion. We let go of Santa Claus by the time we’re ten but the fairy tales, myths and legends of so-called ancient wisdom ascribed to an invisible man in the sky carry on. When you take away a person’s right to come willingly towards whatever light you offer, it ceases to be a faith of his/her own choosing; rather that’s the clear definition of indoctrination.

I’m not an atheist, but I’m a realist and pragmatic. And in being such, I know through personal experience that there is something more to us, but I’m also sure that everyone’s holy book on what that is isn’t correct.

There’s a great verse in the Upanishads, which is a Sanskrit text, but its philosophy is used in Buddhism, Jainism and Hinduism. I’m paraphrasing: “We do not know whether man is the body, in the body or other than the body, whilst alive. How can we know after the death of the body, he is dead?”

For me, that is the sum total of what we’ll ever know about this capsule each of us resides in until we cross into the undiscovered country from whose boon no traveller returns. We just don’t know because despite what the good books may say, or those with near-death experience may feel, no one has died, really died and then returned to tell the tale of what lies in the great beyond.

That’s the answer we want from religion. That’s the one answer it can’t give us. And that’s the greatest story one could ever tell.

Film Courage: What is the one mistake most filmmakers make, regardless of experience?

Maninder: I saw Ron Howard once live in a discussion and he said something along the line of he wishes people knew that directors don’t always have all the answers. Sometimes a good solution can come from a P.A. so you should listen and if it’s a good idea use it and not act too above everyone to do so. I agree with this to a point. But I’ll add trust your gut.. and never leave a scene until you have it. Ever. Unfortunately, budget dictates time.. and every director knows there isn’t time in the world to get everything you want.

Film Courage: What is the hardest thing you’ve ever had to do?

Maninder: My niece, Anjaleen had been born on April 12, 2006. I went to see her a couple days after her birth and then went back to Toronto to produce a small film. Ten weeks went by and I hadn’t gone back, because I was “too” busy getting a silly little project done. On June 24th, I got a call that she had passed away in her crib from a stroke. I think of my nieces and nephews as my own. When you lose a child, a little hole opens up in your heart. It’s a very physical thing, you can feel it happen and no matter what you do… it can never be filled again. So burying her in that little casket was the hardest thing ever. But it taught me one thing: no matter how busy you are, you take time for your family. Family is everything.

Scene from the movie LITTLE TERRORS by Writer/Director Maninder Chana

Film Courage: What’s next for you creatively?

Maninder: I’m working on funding for a couple of features. But I just wrapped post on a heist movie called Scratch. It’ll be out later this year. It’s the complete opposite of Little Terrors. What I’m most proud of, given all this Oscar fervor over #oscarssowhite, is that when I got the script for it, it was completely white-bred. There was not a person of color in it. I rewrote it. My wonderful casting director, Sweeney McArthur asked me about color and I said just get me good actors. We cast two black males in main roles, a black woman in another pivotal one, we have a gay character in a non-stereotypical seminal role, and a singing transvestite in another, who shares most of the back half of the film with Russians, Europeans and Asians and the like along with every other shade I could edge into the centre and corner frames. Hell there’s even a redhead in it. Plus our lead is female. This, as a filmmaker of color, was a natural course for me to take. It is an extension of me. And I think ultimately if directors of color are given the opportunity and budgets to make films they want, this change that so many are craving will come about naturally. But that takes altering the mindset in both the Canadian and U.S. film industry.

BIO:

Maninder Chana (Writer and Director)

Maninder Chana is a multi-faceted personality. From being an award winning writer, director, producer to an actor and musician, he has done it all. Born in India, Chana moved to Canada with his family at the age of five. He grew up in Windsor and calls that an interesting experience ‘given the close proximity to the U.S.’ Beginning his career as a journalist, he soon moved into film and television.

Chana was also the driving force behind Mixed Nuts. The multicultural comedy troupe sold out shows and garnered accolades for its cutting edge humor, and paved the way for a lot of comedians out there. “I see them doing a lot of the same material now,” says Chana.

This experience lent itself to film and Chana did a good number of shorts, all of which played internationally, some winning awards.

The Toronto based director has spent a lot of time on the West Coast, Los Angeles and New York for filmmaking.

As a filmmaker, his projects include the feature films Cell 213 (2011), Mystic (2011) and his latest feature, a dark-comedy heist caper called Scratch that is currently in post-production. He also has a television series optioned with Hollywood talent attached, along with several other projects in the works.

In addition to his screen work, he is an author with an acclaimed short story collection, Gunga Din Lite & Other Delights (of Lust and Comedy).

“The main thing for me is to leave a bunch of good stories behind. I try to do what I love,” says Chana.

CONNECT WITH LITTLE TERRORS MOVIE:

.