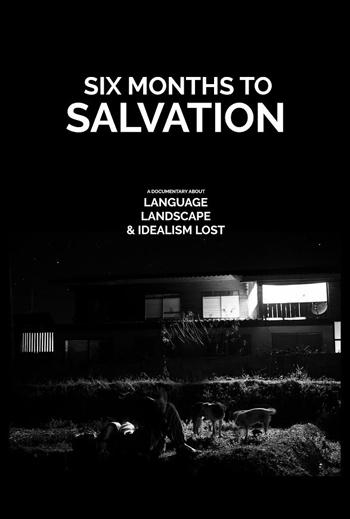

Lorenzo Benitez – Director of Six Months to Salvation

Film Courage: Where did you grow up?

Lorenzo Benitez: I was born in Manila, the capital city of the Philippines, and lived there for the first eight years of my life before my family migrated to Sydney, Australia. I spent my entire adolescence in the latter, which is why I like to think of it as where I did all my real growing up. So despite being born in Manila, I’m much more inclined to call Sydney my “hometown.”

I am the eldest of three children: the other two are still in high school. We have a mother and a father who’re still together. Despite our atypical international upbringing, I’d say we’re otherwise a fairly nuclear family.

In relation to the documentary I’m promoting, I think my preoccupation with the efficacy of charity, which heavily constitutes the film’s investigations, can be traced back to some of my parents’ more unorthodox rearing. While growing up as a kid in Manila, my parents allowed me to keep only two of the gifts I received each Christmas, while the rest were distributed to street children. The same went for my two siblings. And so, every Christmas morning for a number of years, my dad would drive us around in search of families with children. I vividly recall internalizing the belief that because a street child would enjoy any of my toys for a long while whereas I often forget them after a week, I should probably share a lot of my toys.

In relation to the documentary I’m promoting, I think my preoccupation with the efficacy of charity, which heavily constitutes the film’s investigations, can be traced back to some of my parents’ more unorthodox rearing. While growing up as a kid in Manila, my parents allowed me to keep only two of the gifts I received each Christmas, while the rest were distributed to street children. The same went for my two siblings. And so, every Christmas morning for a number of years, my dad would drive us around in search of families with children. I vividly recall internalizing the belief that because a street child would enjoy any of my toys for a long while whereas I often forget them after a week, I should probably share a lot of my toys.

It’s probably a bit simplistic to draw a line between the documentary’s interest in efficient charity and this childhood story, but I still think it’s a possible one.

“In relation to the documentary I’m promoting, I think my preoccupation with the efficacy of charity, which heavily constitutes the film’s investigations, can be traced back to some of my parents’ more unorthodox rearing. While growing up as a kid in Manila, my parents allowed me to keep only two of the gifts I received each Christmas, while the rest were distributed to street children.”

Lorenzo Benitez – SIX MONTHS TO SALVATION

Film Courage: Did your parents lend support toward creativity or encourage another type of career/focus?

Lorenzo: My parents have always been supportive of my creative interests. For example, as a little kid, I used to write short stories – all of which if read today would embarrass me – that a lot of my classmates liked to read. One of my fondest memories from childhood is overhearing my mother proudly tell her friends about my stories. It’s an ethereal memory that still sticks with me to this day.

Film Courage: Where are you currently studying? What is your major?

Lorenzo: I’m currently at Cornell University, where I’m studying for a B.A. as a double-major in Philosophy and Economics. I initially contemplated studying film to some extent, but that probably would’ve been redundant. After all, I think it was Werner Herzog who said that making your debut film is as beneficial as, if not more educational than, any form of film school. Actually, it wouldn’t surprise if there’s a whole list of filmmakers who’ve said something to that effect.

Film Courage: What are your plans after college?

Lorenzo: Hopefully, if all goes well, my fellow producers and I will be together making films, documentary and narrative alike. Preferably with larger, less constrictive budgets.

Watch it on Vimeo for free here!

Film Courage: Was this your first time as a volunteer abroad? What made you want to volunteer?

Lorenzo: This was not my first time. When I was still in high school, I returned to the Philippines as part of a three-week service trip that visited a number of impoverished and marginalized communities in Manila and the surrounding regions. In all earnestness, the cognitive dissonance I sensed between the Manila I saw over those weeks and the Manila I had inhabited for eight years profoundly affected me. So, even though some who’ve watched Six Months to Salvation probably think I have a low regard for overseas volunteer programs, this isn’t the truth. I volunteered for Thailand because I had previously benefited from a very rewarding and, excuse the cliché, eye-opening volunteer experience. Also, I have to admit another factor that influenced my decision was I needed an altruistic reason to justify taking a gap year before starting university.

Film Courage: What were your initial impressions of Thailand?

Lorenzo: I remember initially feeling a little strange to be in another South East Asian nation that visually resembles the Philippines, both in its environment and in its people, but is actually very different. More than once was I mistaken for a Thai person, yet was unable to fluently respond or fully ascertain the idiosyncrasies of Thai culture.

Film Courage: How was the region in which you were staying different from other parts in Thailand?

Lorenzo: I stayed in the Chiang Mai province in northern Thailand. Culturally, I understand that there are some differences between Thai people from the northern parts and Thai people from a different part, such as Bangkok in central Thailand. However, because I spent a majority of my time with the Karen hill tribe, who themselves practice their own distinct culture, I can’t really make any further intranational comparisons.

However, I can tell you that Karen culture has its own language, which is what almost all speak at home, while the language of instruction at school is Thai. In addition to this, they also learn a third language while at school: English, as taught by the volunteers in the film.

The Karen have a long history of being marginalized by dominant Thai society, which has tended to look down on them, along with a lot of the other hill tribes that populate the mountainous regions of the country. They live in small, intimate communities – villages of no more than a few hundred people each – and many derive a living from farming.

Film Courage: What inspired the story for SIX MONTHS TO SALVATION?

Lorenzo: Initially, instead of Thailand, I was going to be stationed in East Timor for six months. I did some research into East Timor and was surprised that the country was yet to be portrayed by popular media as anything more than an exotic tourist destination. Surely East Timor’s recent history is more than enough substance for a fascinating documentary, I thought to myself.

After planning for an East Timor documentary for some time, I suddenly learned that my placement had been moved to Thailand. Originally, I was ready to call off the entire film, thinking that there was nothing of interest to be found in a film about seven Australian teenagers in one of South East Asia’s most-visited countries, which already has a thriving national cinema composed of globally-revered filmmakers.

However, after some thought, I realized that while I could no longer be certain about my subject matter’s originality, it seemed like the bar had been set higher to strive for originality in other ways. In time, I was exposed to some criticism that labeled overseas volunteer programs like the one I had signed up for as neo-colonialist, which led me to consider documenting my own experience. I wanted to provide evidence that could only lead to more informed discussion on the relationship between colonialism and “voluntourism,” and so it wasn’t long before I regained my ambition to make a film.

“The [editing] process clarified something I’ve suspected for a while: that the notion of an authoritarian auteur is really stupid. Creative partnerships do exist, and we like to think of our own film collective as less like three separate filmmakers who cooperate for the sake of financial expediency and instead as one creative voice united by its members’ similar thematic interests, wide-ranging aesthetic sensibilities, and complementary technical skills.”

Lorenzo Benitez – SIX MONTHS TO SALVATION

Film Courage: Can you take us to events leading up to SMTS’ opening scene? Why does it set up the beginning of the film?

Lorenzo: The opening scene is actually a flash-forward to the Easter holidays, which chronologically fall in the middle of the film. Jonathon, one of the editors, was very insistent on starting the film with this scene, which shows me mocking a group of American teenagers who’re making a documentary about their own volunteer trip to Africa. I think it reminded Jonathon of scene in one of his favorite films, Man Bites Dog, when the filmmakers who’ve been making a documentary about a serial killer literally run into another film crew making another documentary about their own serial killer.

I’m glad Jonathon was so insistent, because I now appreciate how our opening scene not only previews the film’s substantive investigation into the impact of “voluntourism,” but also because it immediately complicates the distinction between Lorenzo, the character, and Lorenzo, the filmmaker. It contextualizes myself as a subject, as well as the director. Indeed, my commitment to directorial impartiality inspired me to be just as critical of my own perspective as I was of others.

It’s frustratingly didactic to begin a documentary with the director narrating as if they were a god-like presence, or staring straight into the camera with a sense of bloated authority. We therefore chose to open with that scene because it dismisses the myth of the completely-impartial director, which we felt was a more candid acknowledgement of my unique perspective as someone making a film meant to objectively analyze the impact of volunteering, who also signed up to be a volunteer himself.

SMTS Collaborators Jonathon Parker and James Holloway

Film Courage: Who are your collaborators on SMTS? How did you meet them?

Lorenzo: My fellow producers and editors are James Holloway and Jonathon Parker. Together, we are the film collective u16.co. We are interested in cinematically exploring the broad uncertainties posed by a globalized world, which is we named ourselves after a URL: a ghostly, non-physical entity that reflects our international identity, especially now that I live in New York while the other two live in Sydney.

We all went to the same high school, so we all knew each other long before we made Six Months to Salvation. In high school, I had done a lot of acting alongside James, who I’ve always admired for his creativity and intelligence. Asking him to help me make this film therefore wasn’t hard. Jonathon and I befriended each other after he had already graduated from high school, but we very quickly hit it off with our shared love of cinema. Soon enough, our long conversations about film eventually turned to the possibility of making one together. Fast forward a few years, and here we are.

Film Courage: How did you develop the title Six Months to Salvation?

Lorenzo: We wanted a title that was memorable, pleasant to the ear, and, most importantly, captured the documentary’s essence. Thankfully, the consonance of the letter ‘S’ guarantees the first two. We also included the events of the film’s duration in the title – “Six Months” – because we want audiences to feel as if they were embarking on a temporally significant journey.

The word “Salvation” was harder to come upon, but we ultimately settled on it because we believe it best introduces the film’s thematic focus. Is “voluntourism” really about substantively improving the lives of impoverished people, or is it more about salvaging the consciences of Westerners from the maw of excess? Can either even be achieved in as short a time frame as six months, which itself is already much longer than the majority of packaged volunteering trips?

Film Courage: How old were the children you were instructing?

Lorenzo: I personally taught kids from Kindergarten to Grade Six, and I think most of us did, but James Grant taught at a high school. If I remember correctly, it’s “the highest high school in Thailand,” in that its physical altitude is literally the highest out of all Thailand’s high schools.

Film Courage: Was there anything a student said to you that was especially memorable during your time in Thailand?

Lorenzo: This isn’t exactly something that was said, but on my last day teaching, a lot of my students gave me a bunch of thank you cards with flowers in them. You don’t see this in the film, but it nonetheless significantly affected how I reflected upon the impact of my work.

This kind gesture potentially accounts to some extent for the difference of opinion between Lorenzo, the character, who you see on-camera, and Lorenzo, the director, looking back on the consequence of his volunteer work in the detached suspension of the editing room.

Film Courage: When shooting a documentary, how do you deal with subjects wanting to change their footage, what they said, how they appear, etc? Do you lay down any ground rules before filming?

Lorenzo: Because this was my first attempt at a feature-length film, or a documentary of any length for that matter, I just started shooting my core subjects – the other volunteers – without establishing any real ground rules. In hindsight, I shouldn’t have done this because there were avoidable disagreements on whether something ought to be filmed. Note, though, that anyone who objected to being on camera is not featured in the film.

Thankfully, none of the volunteers refused to be featured in the film. When I asked each of them toward the end of my six months for their formal permission, none requested to be represented in a particular way, or have a particular scene of them omitted. I like to think that after living together for six months, they all trusted me to represent their experiences with honesty and journalistic integrity, even though my personal perspective differed from some of theirs.

Film Courage: What camera(s) did you use?

Lorenzo: I used the Panasonic Lumix GH3. I knew I wanted to shoot on a DSLR because they were all I had ever used to make films. I specifically discovered the GH3 after learning that Shane Carruth shot Upstream Color on a GH2. I then knew we’d found the right camera upon learning that its comprehensive features all fit in such a nimble body. It felt perfect for shooting a cinematic documentary.

Film Courage: What was the budget for SMTS? Biggest expenses for the film?

Lorenzo: The film cost about AU $5,000 (US $3,500) to make, and was entirely funded by our four young executive producers: the three of us from u16.co and our friend Sebastian Perry. The biggest expenses were probably the camera equipment. However, we managed to save a lot of other money elsewhere by selling other equipment the moment we no longer needed it. For example, right after we finished editing, we sold the powerful desktop we bought and re-invested that cash into setting up the film’s online presence. Let’s just say that the money in our budget had a high velocity.

Film Courage: What were some of the biggest challenges to production?

Lorenzo: The biggest challenge was definitely sustaining my personal motivation to shoot over such a long period of time. After all, there’s a scene in the middle of the film when I call Jonathon and say “F*ck it, let’s stop making this film.” I think this is because I didn’t fully grasp the film’s thematic identity until the fifth month. By then, I had accumulated tens of hours of footage but still didn’t sense a satisfying story. Thankfully, as I neared the end of my time in Thailand, I began to recognize that the film’s focus had shifted to something even broader than just the possibility of “voluntourism” as colonialism. We were now asking questions about the ultimate purpose of charity, altruism, and empathy when confronted by its seeming inconsequence.

Another great challenge we faced is less about filmmaking and more specific to the documentary form: giving fair voice to all possible perspectives. How do we balance the perspectives of the seven Western volunteers – which themselves widely vary between, say, Will Noonan and James Grant – and the other Karen people? However, I like to think that we pulled it off because no matter what opinion a potential audience member has of volunteering programs before watching the film, everyone will find something in it that affirms their viewpoint and something that complicates it.

Film Courage: What did you learn from teaching ESL classes?

Lorenzo: Admittedly, with the benefit of more than a year’s hindsight, I learned more from being a teacher than I thought right after my stint ended. The most striking lesson is probably that I am the immensely lucky beneficiary of some crazy privilege. To teach children whose outlooks on life are so unlike my own highlighted the inequity fundamental to all society. I think Ta-Nehisi Coates, in Between the World and Me, uses the term “cosmic injustice” to illustrate the helplessness one feels when confronted by this omnipresent inequity, which begins the moment fortune determines whether we are born into a specific country, of a specific race, gender, and the like.

Film Courage: What did making SMTS teach you about culture and community?

Lorenzo: Making Six Months to Salvation taught me about the malleability of culture and the impossibility of “preserving” it as if it were an insulated museum diorama. My teaching experience taught me that people who vehemently criticize volunteering programs as neo-colonialist are missing two things. First, unlike colonial history, volunteering programs like the one in this film exist because the Karen want their children to learn English: an unignorable exercise of agency missing from colonialist history. Second, as explained in the documentary by Vinai Boonlue, the preservationist notion that certain cultures must remain static instead of naturally interacting with other cultures is not only untenable in a post-globalized world, but also condescendingly suggests that people born into more esoteric, “exotic” cultures ought to be restricted from interacting with the global community in ways that Western, “metropolitan” cultures aren’t.

Film Courage: What did the editing process teach you about creative partnerships?

Lorenzo: The editing process was a roughly three-month-long period during which Jonathon, James and I worked together to stitch the tens of hours of footage into a film with narrative thrust. Many days, we were all present in the room, making committee-style creative decisions. Other days, it was just one of us at the console at a time, doing the menial work of subtitling specific scenes, color-correcting, or mixing sound.

The process clarified something I’ve suspected for a while: that the notion of an authoritarian auteur is really stupid. Creative partnerships do exist, and we like to think of our own film collective as less like three separate filmmakers who cooperate for the sake of financial expediency and instead as one creative voice united by its members’ similar thematic interests, wide-ranging aesthetic sensibilities, and complementary technical skills. The same way musicians, singers and the like can belong to a band while still maintaining their own unique identity, we’d like for u16.co and its members to be regarded similarly.

Film Courage: Favorite moment in the SMTS?

Lorenzo: The final three shots of the film, which together run for a grand total of fourteen minutes.

I honestly like to think that the final fourteen minutes exemplify our best work together as filmmakers. The film’s conclusion is largely the work of Jonathon, who envisioned the penultimate shot being a ten-minute-long static take of the sunset over an empty rice field, and James, who’s responsible for the gradual fade between this penultimate image and the final shot taken from the window of a taxiing airplane. I had the idea of playing a recorded phone conversation over the penultimate shot. Looking back, it all seems like pure creative alchemy.

I actually consider James’ fade to be the most meaningful visual choice in the entire film because, in the most uniquely cinematic way possible, it evinces the spatial and cultural conflation wrought by globalization. Now that we inhabit a world in which one can find humble agrarian life mere hours away from seamless intercontinental travel, the distinction between the two is better represented by a slow fade than a sudden cut.

Film Courage: What does SMTS say about the world we live in?

Lorenzo: Hopefully, it highlights the importance of being introspective and self-critical in an age of other voluntourist experiences that better resemble Kontiki tours. With respect to altruism, we need to be engaged and hold our charitable acts and donations to the same standards of efficacy as any other enterprise. As identified by one critic who enjoyed the film, it’s important that we continue to ask the right questions about how to maximize our impact even when there are no easy answers.

Also, in light of the nationalistic backlash against globalization that has defined much of 2016, hopefully Six Months to Salvation stands as a persuasive example for why the arbitrary borders that separate humans according to geography ought to be further dismantled. The work of the volunteers definitely brought at least some value – to whom and to what extent is open to disagreement – and should therefore be considered as further arguments in favor of broadening our empathy to encompass more than just people from the same country as us.

Film Courage: Where is SMTS available to watch?

Lorenzo: Six Months to Salvation is available for free streaming on Vimeo and YouTube. To find all the relevant links, visit u16.co/6m2s.

Film Courage: Why is SMTS available for free?

Lorenzo: We’ve always known deep down that no one will ever pay for this film. Even with critical praise, as a micro-budget documentary made by a “collective” of really young filmmakers, we just couldn’t anticipate ever finding for it a lucrative market, especially when competing against other films with much larger budgets for people’s time, attention and money.

Also, as a film about the nature of charity that directly features people of disadvantaged backgrounds, we felt like it wouldn’t be right for us to accept cash when that money could be deployed elsewhere in the service of others. So we figured that we might as well cut our losses and make it free.

Film Courage: Are you also submitting SMTS to festivals? Are there any other plans for distribution?

Lorenzo: Nope, this is the end of the line for distribution. If any festivals contact us asking to screen the film in the future, we’d probably say yes, but for now, we aren’t holding our breath.

Film Courage: Can you clarify the terms Westernization and Cultural Preservation?

Lorenzo: The term Westernization, as it is used in the film, refers to the ubiquity of Western, largely white cultural products in the developing world. In Six Months to Salvation you see us eating McDonald’s and witness shots of a Starbucks and an American flag pencil case – icons that litter the landscape in lieu of what might seem to be more ‘authentic’ elements of Thai or Karen culture.

Cultural preservation refers to the attempt to redress such patterns of Westernization. I think it was Schiller who coined the term “cultural imperialism,” whereby originary culture is robbed by the pernicious forces of the West. What Six Months to Salvation explores is whether “voluntourism” threatens attempts at cultural preservation, expedites those attempts, or has an entirely different impact altogether – positive or negative.

Film Courage: What’s next for you creatively?

Lorenzo: James, Jonathon and I are working on a feature-length hybrid documentary about how globalization has disconnected individuals in search of economic opportunity overseas from their families back home, and how people use technology to overcome this divide. The idea emerged because in spite of recent protectionist attitudes that have gained popularity in the West, skilled labor is still able to transcend borders with relative ease. We’re still in pre-production, but we’d like to take recent attitudes toward free trade, foreign employment, and globalization, and charge these sociological constructs with a metaphysical account of the nature and effect of distance.

BIO:

Lorenzo Benitez is the director and cinematographer of Six Months to Salvation, his feature-length directorial debut, in addition to being one of its producers and editors. A 20-year-old Filipino-Australian, he is interested in self-reflexive cinema as a means of exploring the shifting relationship between the developed and developing worlds. He has recently commenced undergraduate studies at Cornell University.

CONNECT WITH LORENZO BENITEZ HERE:

Official site

Vimeo link to watch the film for free

Twitter

Advertisement

Watch ORIGIN on iTunes Starting December 13, 2016

ORIGIN: Three science students are on the verge of making a breakthrough in their research into biohacking and cell aging. When one of them is diagnosed with a terminal illness, they break moral boundaries and use their untested research on him, in an attempt to save his life.

Watch the Indiegogo Campaign video here!

HELLo tHERE takes a dark, but realistic look at the psychological trauma caused by inequality, racism, and homophobia. Our goal is not just to scare the bejesus out of you, but to create a film that is equally terrifying as it is thought provoking. This world is, and has always been, plagued by senseless fear and hatred for one another as human beings. My team and I are fully dedicated to telling stories that showcase the “horrors of reality” in an effort to inspire change.

Watch it on iTunes here!

COLD NIGHTS HOT SALSA takes you inside the international dance world of Victor and Katia, aspiring young salsa dancers from Montreal, who seek to win a World Salsa Championship.

During their three-year quest Victor and Katia draw upon the talents of Eddie Torres, Tito & Tamara, Billy Fajardo, and Katie Marlow. Central figures in the salsa dance world, these mentors put their passion and professional dance skills before you and reveal what it takes to perform and compete at the highest level.

Victor and Katia’s story is a love story. It’s the story of their love to dance and of how being a couple enhances and also complicates their life together and dance ambitions. After winning the Canadian Salsa Championship, we watch as they first compete in the 3rd World Salsa Championship. They return home to Montreal to work on taking their dance skills to a higher level. After months of preparation, including working with a number of key mentors, they put their dreams on the line and travel to Florida to compete in the 4th World Salsa Championship.

Along with Victor and Katia’s story, the film explores some of the social and historical roots of salsa, as told through Eddie Torres, Billy Fajardo, Tito Ortos, and Edson Vallon.

Experience the beauty and excitement of competitive dance, the compelling force of world leaders in salsa, and the romantic charm of two young dancers who want to make their mark on the Latin dance world.

Watch SIX MONTHS TO SALVATION for free on Vimeo here

Six Months to Salvation – This documentary is one of the first feature-length investigations into the burgeoning voluntourism industry, following seven teenagers as they teach English to children in Northern Thailand.

CRUSHED Movie Now on iTunes! – Ellia returns to her family vineyard after her father dies in a winery accident. When his death is ruled a murder and her mother becomes the prime suspect, she’s determined to find the truth. As Ellia uncovers secrets about her family and the winery, she becomes the murderer’s next target.

CRUSHED Movie Now on iTunes! – Ellia returns to her family vineyard after her father dies in a winery accident. When his death is ruled a murder and her mother becomes the prime suspect, she’s determined to find the truth. As Ellia uncovers secrets about her family and the winery, she becomes the murderer’s next target.